- Art.Salon

- Artists

- Roderic O'Conor

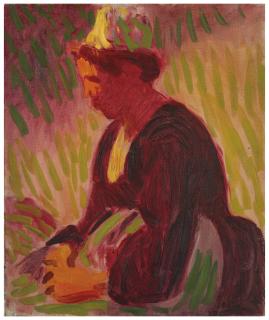

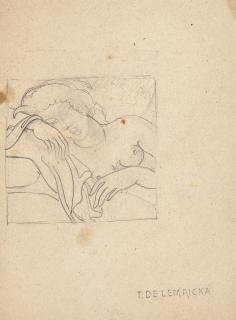

- Peasant woman seated outdoors

Roderic O'Conor

Peasant woman seated outdoors

Estimate: 40.000 - 60.000 EUR

Price realised: 75.600 EUR

Price realised: 75.600 EUR

Description

Le sujet de la paysanne bretonne solitaire, assise à l'extérieur dans le paysage ou à l'intérieur sur un fond neutre, est un sujet que O'Conor s'est approprié à partir de 1892 et jusqu'à ce qu'il quitte définitivement la Bretagne en 1904. Ce choix est inhabituel dans le contexte de l'École de Pont-Aven, où les femmes sont généralement représentées en groupes, soit en train de sociabiliser, soit, plus communément, en train de travailler dans les champs. La tâche d'abstraire le contenu humain d'un tableau est beaucoup plus facile lorsqu'il n'est pas autorisé à devenir le centre d'intérêt principal de la composition. Mais si l'on place une grande figure unique au centre, comme O'Conor l'a fait à plusieurs reprises, le défi pour l'artiste s'accroît proportionnellement: comment éviter que le tableau ne devienne par défaut représentatif et n'ait l'air d'un portrait?

On attend des avant-gardistes de Gauguin qu'ils universalisent leurs figures, qu'ils dépeignent des types de personnages plutôt que des individus (le portrait étant l'objectif des peintres traditionnels qui affluent à Pont-Aven chaque été). Ami et disciple de Gauguin, admirateur de Van Gogh, O'Conor met au point plusieurs techniques pour répondre à ce défi. Au cours de la période 1892-94, alors qu'il a l'habitude d'articuler les surfaces de ses tableaux à l'aide de "bandes" de pigments aux couleurs vives, les visages de ses modèles sont audacieusement intégrés dans la trame linéaire générale. Une autre méthode qu'il privilégiait consistait à demander au modèle de se concentrer sur une tâche manuelle, comme tricoter ou enfiler une aiguille, de manière à ce que son visage soit abaissé et donc projeté dans l'ombre, ce qui brouillait ses traits. Dans le cas présent, l'anonymat a été préservé par un mélange de simplification, où l'artiste se concentre sur l'essentiel) et de pose du modèle en contrejour, de sorte que la majeure partie de son corps reste dans l'ombre. Seuls son corsage blanc et le bord avant de sa coiffe blanche sont exposés au soleil, créant deux accents vibrants qui tranchent avec le rouge alizarine, le vert émeraude et l'ocre qui couvrent le reste de l'image.

La peau tannée et le tablier couleur d'herbe de la jeune bretonne d'O'Conor semblent faire d'elle un prolongement naturel du paysage, au même titre que les Èves tahitiennes de Gauguin (dont un exemple majeur, Te nave nave fenua, était entré dans la collection de l'Irlandais en 1895). Bien qu'accolés au plan focal, les traits impénétrables de la Bretonne conservent un certain éloignement, un sentiment d'appartenance à une tradition culturelle alternative à la nôtre. Cette aura d'altérité est renforcée par une technique résolument non conventionnelle. En n'essayant pas de dissimuler ses coups de pinceau impétueux, appliqués sur des lavis de couleur dilués, O'Conor a délibérément ignoré les normes acceptées de l'art pictural de la fin du XIXe siècle. Il faudra attendre un nouveau siècle et l'avènement d'un nouveau groupe d'artistes, les Fauves, pour que la peinture à l'huile soit à nouveau manipulée avec une telle énergie.

Jonathan Benington

The subject of the solitary Breton peasant woman, seated outdoors in the landscape or indoors against a neutral background, was one that O'Conor explored between 1892 and 1904, when he left Brittany for good. It was an unusual choice within the context of the Pont-Aven School, where women were generally depicted in groups, either socialising or, more commonly, working in the fields. The task of abstracting the human content of a picture was much easier when it was not allowed to become the main focus of the composition. Put a large single figure at the centre, however, as O'Conor repeatedly did, and the challenge for the artist grew proportionately: how to prevent the painting defaulting to representation and looking like a portrait?

Gauguin's avant garde followers were expected to universalize their figures, to depict character types rather than individuals (portraiture being the objective of the traditional painters who flocked to Pont-Aven every summer). As a friend and disciple of Gauguin and an admirer of Van Gogh, O'Conor devised several techniques by which to respond to this challenge. During the period 1892-94, when he habitually articulated the surfaces of his pictures using 'stripes' of brightly coloured pigment, his models' faces were daringly integrated into the all-over linear web. One of his stylistic approaches was to make the model concentrate on a manual task such as knitting or threading a needle, so that her face would be lowered and thus cast into shadow, thereby blurring her features. In the present work, however, anonymity has been preserved by a mixture of simplification (focusing on the essentials) and posing the model with bright sunlight behind her (or contrejour), so that most of her body remains in the shade. Only her white bodice and the leading edge of her white cap are allowed to catch the sunrays, creating two vibrant heightenings that stand out against the alizarin crimson, emerald green and ochre covering the rest of the picture.

The tanned skin and grass-coloured apron of O'Conor's young Breton woman make her seem as much a natural extension of the landscape as Gauguin's Tahitian Eves (a major example of which, Te nave nave fenua, had entered the Irishman's collection in 1895). Despite being pushed right up against the focal plane, the Breton woman's inscrutable features retain a certain remoteness, a sense of belonging to a cultural tradition alternative to our own. This aura of otherness is reinforced by the resolutely unconventional technique. By not making any attempt to disguise his impetuous brushstrokes, which have been applied over diluted washes of colour, O'Conor wilfully ignored the accepted norms of late 19th Century picture-making. It would take a new century and the advent of a new group of artists, the Fauves, before oil paint would again be handled with equivalent energy.

Jonathan Benington

- Atelier de l’artiste; sa vente, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 7 février 1956. | Roland Browse & Delbanco, Londres (probablement acquis au cours de cette vente). | Sam Josefowitz, Pully (acquis auprès de ceux-ci en novembre 1960). | Puis par descendance aux propriétaires actuels.

On attend des avant-gardistes de Gauguin qu'ils universalisent leurs figures, qu'ils dépeignent des types de personnages plutôt que des individus (le portrait étant l'objectif des peintres traditionnels qui affluent à Pont-Aven chaque été). Ami et disciple de Gauguin, admirateur de Van Gogh, O'Conor met au point plusieurs techniques pour répondre à ce défi. Au cours de la période 1892-94, alors qu'il a l'habitude d'articuler les surfaces de ses tableaux à l'aide de "bandes" de pigments aux couleurs vives, les visages de ses modèles sont audacieusement intégrés dans la trame linéaire générale. Une autre méthode qu'il privilégiait consistait à demander au modèle de se concentrer sur une tâche manuelle, comme tricoter ou enfiler une aiguille, de manière à ce que son visage soit abaissé et donc projeté dans l'ombre, ce qui brouillait ses traits. Dans le cas présent, l'anonymat a été préservé par un mélange de simplification, où l'artiste se concentre sur l'essentiel) et de pose du modèle en contrejour, de sorte que la majeure partie de son corps reste dans l'ombre. Seuls son corsage blanc et le bord avant de sa coiffe blanche sont exposés au soleil, créant deux accents vibrants qui tranchent avec le rouge alizarine, le vert émeraude et l'ocre qui couvrent le reste de l'image.

La peau tannée et le tablier couleur d'herbe de la jeune bretonne d'O'Conor semblent faire d'elle un prolongement naturel du paysage, au même titre que les Èves tahitiennes de Gauguin (dont un exemple majeur, Te nave nave fenua, était entré dans la collection de l'Irlandais en 1895). Bien qu'accolés au plan focal, les traits impénétrables de la Bretonne conservent un certain éloignement, un sentiment d'appartenance à une tradition culturelle alternative à la nôtre. Cette aura d'altérité est renforcée par une technique résolument non conventionnelle. En n'essayant pas de dissimuler ses coups de pinceau impétueux, appliqués sur des lavis de couleur dilués, O'Conor a délibérément ignoré les normes acceptées de l'art pictural de la fin du XIXe siècle. Il faudra attendre un nouveau siècle et l'avènement d'un nouveau groupe d'artistes, les Fauves, pour que la peinture à l'huile soit à nouveau manipulée avec une telle énergie.

Jonathan Benington

The subject of the solitary Breton peasant woman, seated outdoors in the landscape or indoors against a neutral background, was one that O'Conor explored between 1892 and 1904, when he left Brittany for good. It was an unusual choice within the context of the Pont-Aven School, where women were generally depicted in groups, either socialising or, more commonly, working in the fields. The task of abstracting the human content of a picture was much easier when it was not allowed to become the main focus of the composition. Put a large single figure at the centre, however, as O'Conor repeatedly did, and the challenge for the artist grew proportionately: how to prevent the painting defaulting to representation and looking like a portrait?

Gauguin's avant garde followers were expected to universalize their figures, to depict character types rather than individuals (portraiture being the objective of the traditional painters who flocked to Pont-Aven every summer). As a friend and disciple of Gauguin and an admirer of Van Gogh, O'Conor devised several techniques by which to respond to this challenge. During the period 1892-94, when he habitually articulated the surfaces of his pictures using 'stripes' of brightly coloured pigment, his models' faces were daringly integrated into the all-over linear web. One of his stylistic approaches was to make the model concentrate on a manual task such as knitting or threading a needle, so that her face would be lowered and thus cast into shadow, thereby blurring her features. In the present work, however, anonymity has been preserved by a mixture of simplification (focusing on the essentials) and posing the model with bright sunlight behind her (or contrejour), so that most of her body remains in the shade. Only her white bodice and the leading edge of her white cap are allowed to catch the sunrays, creating two vibrant heightenings that stand out against the alizarin crimson, emerald green and ochre covering the rest of the picture.

The tanned skin and grass-coloured apron of O'Conor's young Breton woman make her seem as much a natural extension of the landscape as Gauguin's Tahitian Eves (a major example of which, Te nave nave fenua, had entered the Irishman's collection in 1895). Despite being pushed right up against the focal plane, the Breton woman's inscrutable features retain a certain remoteness, a sense of belonging to a cultural tradition alternative to our own. This aura of otherness is reinforced by the resolutely unconventional technique. By not making any attempt to disguise his impetuous brushstrokes, which have been applied over diluted washes of colour, O'Conor wilfully ignored the accepted norms of late 19th Century picture-making. It would take a new century and the advent of a new group of artists, the Fauves, before oil paint would again be handled with equivalent energy.

Jonathan Benington

- Atelier de l’artiste; sa vente, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, 7 février 1956. | Roland Browse & Delbanco, Londres (probablement acquis au cours de cette vente). | Sam Josefowitz, Pully (acquis auprès de ceux-ci en novembre 1960). | Puis par descendance aux propriétaires actuels.