David Torres: Sculptures made of »white gold«

The great cities of the world are shaped by an ever-changing society, and the arts thereby function as a mirror of their changing inhabitants. In this interview series, we let three artists talk whose lives between cultures have brought out exciting artworks.

*Para leer el texto en español, por favor sigue bajando la página!*

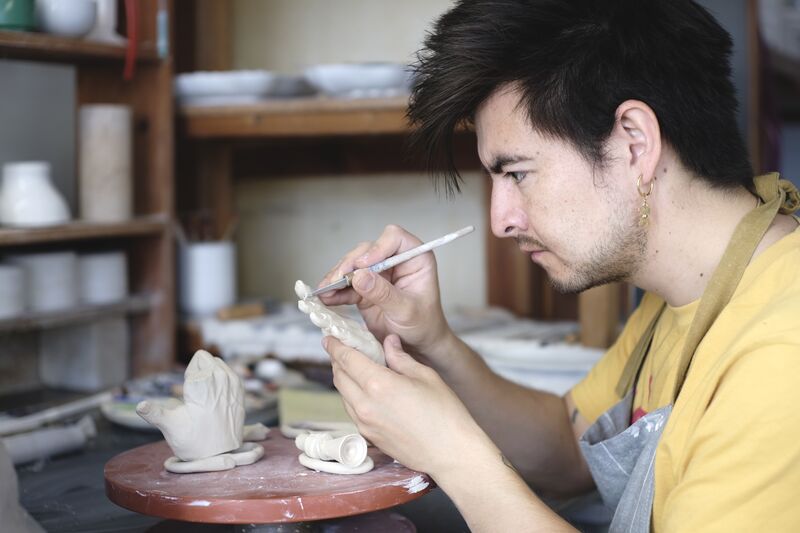

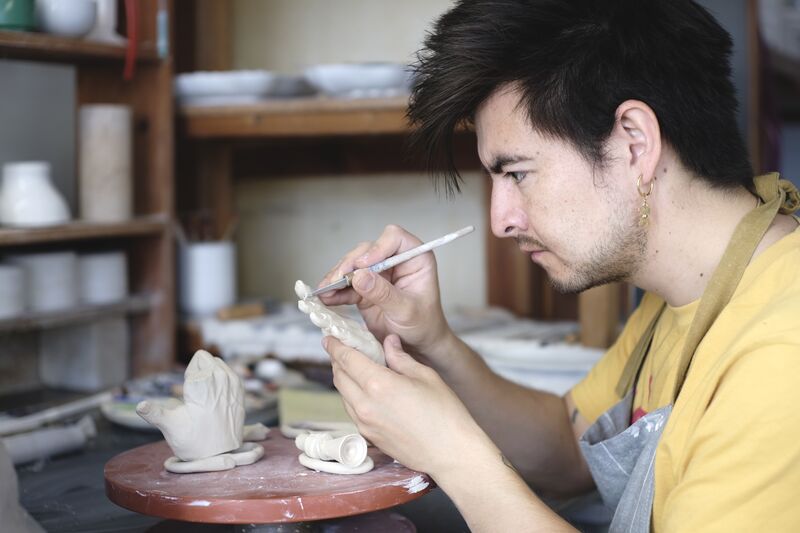

Admitting that certain clichés are true hurts - it hurts even more when one's own identity is questioned. In his current work, ceramic artist David Torres exaggerates the prejudices to which he is regularly confronted as a Colombian and moreover he examines how much truth actually lies behind them.

In the following interview, the artist frankly talks about the influence of the drug trade on Colombia's visual arts, and he reveals to us the history of porcelain from a perspective that only few people know.

I do not often meet artists who work with porcelain or pottery. First of all, how did you come to this technique and what do you like about it?

I started working with ceramics because my father had a porcelain factory for about 40 years with many employees and since I was born I was always in the middle of this factory. That was in the 90s. We lived on the top floor of the factory and every day when I went downstairs there were all these people working, making molds and reproducing my father's designs. But I never looked at porcelain as something I wanted to devote myself to - rather, it was something I grew up with. Of course I looked at it and respected it a lot, but for me it was everyday life.

When I started studying art, I experimented with different techniques like drawing, painting, woodwork, video, etc. and I realized that always at the end of the semester or when I was doing the most important work at the university, I spent most of my time modeling, with ceramics or porcelain; but by instinct, not because it was the material I liked the most. I always felt that the solution to this situation was more to be found in ceramics or porcelain because it is an activity that I have mastered - even if not to perfection - but I knew the process and had free access to my father's studio.

That's why, after I finished my bachelor's degree, I worked on a project in a city in the north of Colombia called San Bacilio de Palenque. The main goal was not really to do something with pottery, but when I visited Palenque I found out that there was a tradition that the inhabitants had many years ago which consisted of going to the river where the women washed their clothes and the children made clay toys and at the end of the afternoon, the water of the river would take their toys back. And that metaphor seemed very beautiful to me, but they were stories, they were not things that I had seen. I thought it was an interesting possibility to let this activity exist again. So the project consisted of meeting with children and teenagers, inviting them to play in the Arroyo, make our toys and as a closure to give life to those objects they made in clay and turn them into ceramics through the construction of an earth oven made together with the community.

In that moment I felt that ceramics is not only a formative technique for me, but also a part of my thinking. It is not only a method to realize a work, but it is part of the conceptual universe of the things I create. Later, after I got my bachelor's degree, I experimented a lot. I worked at home in the studio in a very empirical way to find out what the possibilities of the material were, because I never really had classes in ceramics. I only had the knowledge that my father passed on to me, and this knowledge was not academic or theoretical, but was acquired in an experimental way. For example, my father knew how to operate the kiln, but he didn't understand the temperature curve and what the changes were. He understood to some extent that there were technical things that needed to be done, but he didn't know the reason behind them.

And how did your father learn this craft?

In Colombia, between the 70s and 80s, there was a place called »La Clínica de la Porcelana« where porcelain was restaurated. The director of the place started importing materials and making porcelain. I think that he studied in Italy and made the first porcelain in Colombia with materials from Europe. A brother of my father worked there, learned the craft and then explained it to my father. But then this voice-to-voice teaching was not 100% complete.

So I learned what my father taught me, but I didn't know how things worked. So it was a very specific way of learning, but still valid. After my fine arts studies, I felt like I knew ceramics, but I reached a point where I needed to understand it better. Because to elaborate larger objects one has to know about other techniques and materials.

Then I found out that there was a scholarship in Germany to study for a master's degree, and I looked for a university that taught mainly ceramics. I studied in Höhr-Grenzhausen (Koblenz University of Applied Sciences), a university that has a master program in ceramics and glass. There you enter a world where everything is possible, because they explain how to make your own ceramic glazes, what are the components of each glaze, what are the components of ceramics and porcelain, what about safety (because there are materials that are very toxic and harmful to the environment). So I took this path.

Could you imagine working with other materials?

I think the strongest thing I have is modeling. The possibility to shape works with my hands, especially in clay, is my space where I feel very comfortable and where I can realize all my ideas. So I think porcelain and ceramics are the appropriate mediums for me with which I can do my sculptures. But I don't want to be a person dedicated only to pottery.

There is a very important question that my university professor, Markus Karstieß, asked me and kept reminding me of: Is it really necessary to make the piece in ceramics? Because the process is so complex that sometimes it is even easier to make a piece in another material. You always have to ask yourself if the artwork really needs to be made in that material.

A pottery work has its own language, and for me it has to be consistent with the message. It is very simple to use the material for its beauty, its brilliance or its fragility, but I think there must be a solid association between the concept and the materiality of the ceramic or porcelain.

That is very interesting, because artists who work with other materials, for example painters, don't have to ask themselves whether it's worth using oil paint or canvas before they start a project. Because these materials are usually not as expensive as those used by ceramists. By asking yourself these questions, you show that you realy value the material.

I have one more question: In Germany, there is sometimes a very strict distinction between art and craft. What do you think about this distinction?

This is a very difficult question.

I know that in the USA, for example, ceramicists are valued and shown in art exhibitions. That's probably because of the culture there. I have the feeling that in Colombia, for example, ceramics is still seen as something handmade. In Germany, it can be both craft and exhibition art, depending on the context of the object you are making.

I think, for example, that the things that are made in porcelain factories in Germany are crafts. On the other hand, not the fact that something is handmade is a disparagement of the craft, however, it has been thought and worked on by several minds and one main artist. I think that this kind of art is not so strong conceptually. They have an undeniable and unparalleled beauty, but conceptually they remain a decorative object.

But in these factories, there are often opportunities for external artists to do projects with the material and then the piece becomes a work of art. One example is Damien Hirst, who went to the Nymphenburg factory and made pieces that have to do with his own work, with his own conceptual content and with his own iconography. Also I like to mention Ai Weiwei with the sunflower seeds in porcelain that he did for the Tate Modern Gallery. These artists can use the material to their advantage. In this case, I think it's a work of art.

But I think these crafts are also very important because they tell the story of the moment they were made. For example, if you go to Meißen and have a look at the pieces from 1710 to today, you can see what happened in all that time.

The same is true of pre-Colombian ceramics in Colombia. Before the Spanish came to murder and steal, there was a legacy of ceramics that we don't really know if it was art or craft. They made things simply because they were part of their religion and their customs. I think it's very important to talk about their symbolism and iconography. That's why, as an artist, I don't only dedicate myself to artworks, but I also make everyday objects. For this reason I work with popular culture, which I consume myself.

I know the traditional pottery in Colombia, for example from Ráquira. But how did porcelain come to Colombia and how did people start to produce it there?

The porcelain came, if I'm not mistaken, through the »Clínica de la Porcelana«, the factory we were talking about. It was a place that was not really used to make our own Colombian porcelain, but to make copies of European porcelain. Because the people who were making these pieces were actually pursuing monetary goals, not artistic ones.

In the 1980s and 1990s, most of the people who had great economic power in Colombia had connections to the drug trade. These people wanted to acquire social prestige because they became millionaires from one moment to the next. And how do you do that? Well, with the things that surround you: expensive houses, expensive cars, porcelain imported from Europe that only Europeans have. In reality, however, it was porcelain with European motifs made in Colombia and sold at exorbitant prices. Many sellers, but not the factories, became millionaires as a result of this phenomenon. There was a system in which the factory simply produced and independent people who did not work for the factory sold the porcelain to their customers at 10 or 20 times of the factory price. So the contact between the customer and the factory was not direct, but there was an intermediary.

That's why the porcelain trade in the 80s and 90s was closely linked to the cocaine boom in Colombia. That's a subject I'm very excited to explore.

That's right, you are working on this topic right now. Please tell us what exactly you are doing and what is the idea behind your current work.

Well, a few months ago I applied for a competition called »Richard-Bampi-Preis«, I was selected and the pieces of my master thesis were exhibited. One of the prizes for this competition was a residency at the Porzellanmanufaktur Meißen, the icon of German opulence. There the porcelain recipe was discovered in 1708. Actually, the origins of porcelain are in China, but in Meißen the recipe was developed in a laboratory. And I had the opportunity to do my artist residency there.

I thought it was relevant to talk about the relationship between porcelain and cocaine. In Germany they say »white gold« to porcelain and in Colombia they say the same thing to cocaine: the same expression is completely different in the two countries. But for me it means both because I am at home in both places and the history of porcelain is connected to my family in that sense. So I'm making a work that relates to the cocaine problem in Colombia, and that is connected to the history of my family's porcelain.

The idea was to make a work in the residence and I have always had an interest in my name David and my identity and in the different David's that have marked history. For this reason I have made David Bowies or Michelangelo in mugs and when I started to think about what to do in Meißen I said: maybe it's time to make a David Torres in porcelain. What could be more Kitsch than making oneself in porcelain? (laughs)

If we are already in a place where Kitsch is represented in some way in Europe, then this has to be completely Kitsch (laughs).

So I'm going to put certain details that generate a little bit of discussion. I am in love with popular culture, especially reggaeton, its aesthetics and everything that is part of it. There are many people who love reggaeton and there are people who hate it, so it's like being in limbo. So if I make a David reggaetonero, it's like showing a little bit of the exaggerated and kitsch aesthetics that I'm interested in at the moment.

It also has a lot to do with the aesthetics of the drug trade. In reggaeton videos you see people with a lot of gold and money showing their wealth ...

If it's an autobiographical work, it seems logical to me that you use symbols that represent your biography, yourself and Colombian culture, which also includes this aesthetic.

Yes, that's part of what makes me Latino. Reggaeton is Latin American. Besides, the aesthetic of famous reggaetoneros is to show what they have, and that's what the first drug dealers wanted too. This exaggeration was what was significant to me.

It's also kind of an allegory for how we're seen abroad. Sometimes people think that all these preferences come from me, but I'm not like that. I don't use cocaine either. But always when I'm asked where I'm from and I answer that I'm Colombian, the first thing many people associate me with is drug trafficking and Pablo Escobar. All these things come from movies and series that have to do with drug trafficking. And that's how people see us.

I don't know if it's right to identify with that. Should we just stay quiet because the country is actually undeniably connected to that? You can't cover the sun with one finger.

So the work is an exaggeration of myself, but also an exaggeration of this iconography: the »grills«, the huge »blingbling« and these jackets full of colors and prints with many simbols. At the prints on the jacket of the self-portrait, there are some elements that directly relate to the events or the Narco aesthetic that developed in the 90s. I'm not so much interested in narcos or cocaine nowadays, but more in what was happening at the time when my father was working with porcelain and how the drug trafficker phenomenon was portrayed at that time. The whole country was affected by it in a way. So many bad things happened and no one could talk because of the fear. Life just went on despite all these circumstances. So the idea is that all this iconography, like the jacket, is part of the imaginary.

I also play with the theme of brands, which is why I confront the crossed swords of the Meissen logo with two crossed pistols, which represent the Narco aesthetic. I was a bit afraid to be so straightforward with such things, especially that Meißen might misunderstand me. But they show understanding of where I'm coming from and what exactly I want to tell. It's a story that very few people know, and I find it very exciting how the aesthetics of the drug trade have permeated so many areas of visual art in Colombia.

The piece is in process and will be finished in the next few days; in June or July 2023 there will be an exhibition with my colleagues where I will show the result of the residency. The piece still needs to be decorated and a final firing in the kiln.

What do you think are the current challenges for ceramic artists?

Well, one of the challenges one has as a ceramic artist is not to be pigeonholed. In my networks I say that I am a ceramist, but I don't want to be labeled as one. The language of art must also speak through other materials and other experiences. In my opinion, nowadays it is important for ceramicists to deal with technologies as well. It is important to know that we are not just craftspeople who put things in a showcase, but that our works are worthy of being in an important exhibition space.

There is another very important point, especially in Europe, which has to do with the cost of raw materials and energy, because we all know that clay is fired in a gas oven or in an electric oven. Now that Ukraine is in the middle of war, Germany is directly affected by energy problems, and the cost of electricity or gas has doubled or tripled. As a Colombian artist who has nothing to do with Ukraine, this affects me directly. The artists who are not exactly wealthy are very scared, also in the bigger companies like Meißen or Hedwig Bollhagen, where I work we try to rethink a lot because the costs are so prohibitive or one day there might be no gas. So the question is how to reduce costs and energy consumption. The prices of the raw materials, all the colors and glazes have gone up exorbitantly because they are minerals, and all that is mining. One of the biggest challenges is to reduce the impact of consumption in the production of the pieces, to use 100 percent of the materials and to use the kilns more efficiently, for example, by investing in better kilns that spend less energy. I think that for an artist who is mainly dedicated to ceramics, it is a very big challenge to make things more sustainable.

For me it is very interesting that as ceramists, you have to slow down the artistic processes and also our habits of how we look at art have to slow down. I think this problem is very relevant, considering the way we interact with social media today.

Yes, you have to think about whether it's worth it, not only in terms of cost and time, but also of the idea. You can have many ideas, but are you aware of the economic and energy prices? When I talk about my ideas, some people say, »It's just a matter of doing it, just do it!«. But it is not wise to realize all the ideas I come up with because the ceramic materials I use are not cheap at all. I also realize that there are artists who make works on current topics in a very fast way. And if I wanted to make a work about the war between Russia and Ukraine, for example, it would be possible that the war would even end and I would still be in the middle of the process. Because the processes that I elaborate are really long term (laughs).

David, thank you for the interview and we look forward to seeing the results of your current work!

David Torres

Website: https://www.liebertee.de/david

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/davidftorres/

David Torres: Esculturas de »oro blanco«

Las grandes ciudades del mundo están marcadas por tener una sociedad en cambio constante, y las artes funcionan como un espejo de sus habitantes en permanente mudanza. En esta serie de entrevistas, damos la palabra a tres artistas cuyas vidas entre las diferentes culturas han producido obras fascinantes.

Admitir que ciertos estereotipos son ciertos, duele. Y duele aún más cuando estos cuestionan la propia identidad. En su obra actual, el ceramista David Torres exagera los prejuicios a los que se ve regularmente expuesto como colombiano e investiga también cuánto hay de verdad detrás de ellos.

En la siguiente entrevista, el artista habla abiertamente de la influencia del narcotráfico en las artes plásticas colombianas y nos revela la historia de la porcelana desde una perspectiva que poca gente conoce.

Rara vez me encuentro con artistas que trabajen con porcelana o arcilla. Primero, ¿cómo llegaste a esta técnica y qué te gusta de ella?

Yo empecé a trabajar con cerámica porque mi padre tuvo una fábrica de porcelana con muchos empleados por 40 años aproximadamente, y estuve toda mi vida desde que nací en medio de esa fábrica. Esto era en los años 90 y nosotros vivíamos en el último piso de la fábrica y todos los días cuando bajaba encontraba a toda la gente trabajando, algunos haciendo moldes, otros modelando los diseños que mi padre creaba. Pero yo nunca vi la porcelana como algo a lo que me quisiera dedicar porque fue algo con lo que me relacioné desde que nací. Obviamente miraba y respetaba mucho la labor, pero para mí era vivir en la normalidad.

Cuando empecé a estudiar artes experimenté con diferentes técnicas como el dibujo, la pintura, trabajo con madera, con video, etc. Y me di cuenta de que siempre para los cierres del semestre o en los trabajos más importantes de la universidad, el recurso al que siempre aludía era el modelado. Pero por instinto, no porque fuese el material que más me gustaba. Sentía que la solución de la situación se podría resolver con mayor practicidad en cerámica o en porcelana porque es una actividad que yo domino, no a la perfección, pero conocía el proceso y tenía acceso libre al taller de mi padre.

Por eso después de mi graduación, trabajé en un proyecto artístico en un pueblo del norte de Colombia llamado San Basilio de Palenque. El objetivo principal no era la cerámica, durante una visita que hice a Palenque me enteré que había una tradición que tenían los Palenqueros años atrás la cual consistía ir al arroyo donde las mujeres lavaban la ropa y los niños hacían juguetes de arcilla y al final de la tarde, el agua del arroyo se tomaba de regreso sus juguetes . Y esa metáfora me pareció muy bella, pero eran historias, no eran cosas que había visto. Me pareció interesante darle la oportunidad a esta tradición de volver a existir. Entonces el proyecto consistió en reunirse con niños y jóvenes, invitarlos a jugar al Arroyo, hacer nuestros juguetes y como cierre darle la vida a esos objetos que hacían en arcilla y convertirlos en cerámica a través de la construcción de un horno de tierra hecho con la comunidad.

En ese momento entendí que la cerámica no es sólo una técnica artística para mí, sino que también hace parte de mis pensamientos. No es sólo la técnica para realizar una obra, sino que forma parte del universo conceptual de las cosas que estoy creando.

Y luego, cuando terminé el Bachelor hice muchos experimentos. Estaba en el taller en la casa, simplemente trabajando para descubrir los alcances del material de una forma muy empírica, porque yo realmente nunca recibí clases de cerámica. Solamente tenía los conocimientos que mi papá me había transmitido y esos conocimientos de mi papá no eran académicos ni teóricos, sino eran aprendidos en una forma bastante empírica. Por ejemplo, mi papá sabía cómo prender el horno y usaba los conos de temperatura, pero él no entendía la curva de temperatura que uno puede poner al horno y que a través de los cambios la cerámica y los esmaltes pueden comportarse de formas diferentes. El entiende hasta cierto punto, había cosas técnicas que se hacían pero que no se comprendía.

¿Y cómo aprendió tu padre esta profesión?

En Colombia, entre los años 70 y los años 80, había un sitio que se llamaba »La Clínica de la Porcelana« que era un sitio donde restauraban porcelana. El jefe del sitio empezó a importar materiales y producir porcelanas. Tengo entendido que esta persona estudió en Italia e hizo las primeras porcelanas en Colombia con materiales europeos. Un hermano de mi papá trabajó allá, aprendió y luego enseñó a mi papá. Pero entonces esta enseñanza voz a voz no era 100% completa.

Entonces yo aprendí por mi padre, pero no entendía el por qué de varias cosas. Fue una forma de aprender muy particular, pero igual completamente válida. Después de mi estudios de bellas artes, sentía que conocía la cerámica, pero había llegado a un punto en el que necesitaba entenderla mejor. Porque para elaborar objetos más grandes uno tiene que saber sobre técnicas y materiales diferentes.

Entonces descubrí que había una beca en Alemania para hacer un Master y busqué una Universidad que impartiera clases de cerámica específicamente. Entonces estudié en Höhr-Grenzhausen (Hochschule Koblenz) que es una universidad donde hay un Master en cerámica y vidrio y allí uno llega a un mundo donde cualquier cosa es posible. Porque aprendes a crear tus propios esmaltes, el tipo de componentes tiene cada esmalte, qué componentes tiene la cerámica, la porcelana, aprendes también sobre la seguridad (porque hay materiales que son muy tóxicos y contaminantes). Y así fue el camino que se realizó.

¿Podrías imaginarte trabajar con otros materiales?

Siento que mi fuerte es el modelado. La facilidad que tengo con los manos de modelar piezas, sobre todo en arcilla es mi espacio donde me siento muy cómodo y donde puedo dar la vida a todas las ideas. Entonces, siento que la porcelana y la cerámica son los materiales adecuados con los que yo puedo hacer mis modelados. Pero sin embargo no quiero ser una persona que se dedica solamente a la cerámica.

Hay una pregunta muy importante que me hizo un profesor en la universidad que se llama Markus Karstieß, que siempre me recordaba, ¿si es necesario hacer la pieza en cerámica? Porque el proceso de la cerámica es tan complejo que a veces es incluso más fácil hacer una obra en otro material. Hay que preguntarse siempre si la obra necesita ser de ese material.

Una obra en cerámica tiene un lenguaje propio y para mi debe ser coherente con el mensaje. Es muy simple usar el material por lo bello, por lo brillante o por el frágil, pienso que debe haber una asociación sólida entre el concepto y la materialidad de la cerámica o de la porcelana.

Esto es muy interesante, porque los artistas que trabajan con otros materiales, por ejemplo los pintores, no tienen que preguntarse si vale la pena utilizar óleo o lienzo antes de empezar un proyecto porque estos materiales no son normalmente tan caros como los que utilizan los ceramistas. Al hacerse estas preguntas, demuestra que realmente valoras el material.

Tengo otra pregunta: En Alemania, a veces se hace una distinción muy estricta entre arte y artesanía. ¿Qué opinas de esta distinción?

Es muy difícil la pregunta.

Tengo entendido que por ejemplo en los EE. UU. los ceramistas son respetados en el mundo del arte expositivo. Es así seguramente por el tipo de cultura que hay allá. Tengo la sensación de que por ejemplo en Colombia todavía la cerámica es vista como algo artesanal. Y en Alemania puede ser tanto artesanal como puede ser arte expositivo, dependiendo del contenido que le pongas al objeto que realizas.

Por ejemplo, tengo la sensación de que las cosas que se hacen en las fábricas de porcelana en Alemania son artesanía. Por otro lado, no necesariamente el hecho de que algo sea artesanal esté en un escalón abajo del arte, sino que son pensadas y trabajadas no solamente por una cabeza y un artista principal.

Creo que conceptualmente no son tan fuertes. Tienen una belleza innegable e incomparable, pero conceptualmente se quedan en un objeto decorativo. Pero en estas empresas hay artistas que vienen y hacen proyectos con el material y allí es cuando la pieza empieza a ser una pieza de arte. Por ejemplo, artistas como Damien Hirst en Nymphenburg que han ido a la fábrica y que han hecho piezas que tienen que ver con su propia obra, con su propio contenido conceptual, con sus iconografías y pueden utilizar este material en su beneficio. O incluso Ai Weiwei con las semillas de girasol en porcelana que hizo para la Tate Modern Gallery. Allí es cuando pienso »eso es una obra«.

Pero igual me parece muy importante todas esas artesanía porque cuentan el momento histórico en donde se ubican. Por ejemplo, cuando uno va a Meißen y ve las piezas desde 1710 hasta la actualidad uno observa que paso en todo este tiempo.

Lo mismo pasa en la cerámica precolombina en Colombia. Antes de que llegaran los españoles a masacrar y a robar había un legado de piezas en cerámica valioso que en ese entonces no se consideraba la división entre arte o artesanía. Simplemente hacían las cosas porque hacían parte de su idiosincrasia y creencias. Hablar de su simbología y de su iconografía me parece muy importante. Por eso yo, como artista, no solamente me dedico a hacer obra expositiva, sino que también hago cosas utilitarias porque son parte de mi día a día, y por eso trabajo con la cultura popular que yo consumo.

Conozco los tradicionales trabajos en barro de Colombia, por ejemplo, de Ráquira. Pero ¿cómo llegó la porcelana a Colombia y cómo llegó la gente a fabricarla allí?

La porcelana llegó, si no estoy mal, a través de la »Clínica de la Porcelana«, que es el taller del que hablamos. Era una fábrica de piezas que realmente no era para hacer nuestras propias porcelanas colombianas, sino para hacer réplicas de porcelanas europeas. Porque realmente el objetivo de las personas que estaban haciendo estas piezas eran objetivos monetarios, no eran artísticos.

En los años 80 y 90 la mayor cantidad de gente que tenían mucho poder económico en Colombia tenían nexos con el narcotráfico. Esta gente quería construir status social porque de un momento a otro se volvieron millonarios. ¿Y de qué manera uno construye un estatus social? Pues, con las cosas que te rodean: casas costosas, carros costosos, porcelana importada de Europa que solamente tienen europeos. Pero realmente eran porcelanas hechas en Colombia con diseños europeos y empezaron a venderse con precios exorbitantes. Los que aprovecharon este fenómeno fueron los vendedores independientes de las porcelanas que compraban en nuestro taller y otros. El sistema consistía en que la fábrica producía y vendedores independientes que no trabajaban para las fábricas conseguían sus clientes y vendían las porcelanas a 10 o 20 veces de lo que costaba en la fábrica. Entonces realmente el contacto del cliente y de la fábrica no era directo sino que había un intermediario.

De esta manera el comercio de la porcelana en los años 80 y 90 tuvo mucha relación con el auge de la cocaína en Colombia. Es un tema que me gusta mucho explorar.

De verdad, estás trabajando en este tema en este momento. Díganos qué está haciendo exactamente y cuál es la idea en la que se basa tu trabajo actual.

Bueno, hace unos meses he aplicado en un concurso que se llama »Richard Bampi Preis«, quedé seleccionado y se expusieron las obras de la tesis de mi Maestría en ceramica. Entre los premios que había para este concurso fue participar en una residencia en la fábrica de porcelana Meißen la cual es un Icono de la opulencia en Alemania. Fue en donde se descubrió la receta de porcelana en 1707. Pues, en China nació la porcelana, pero en Meißen se elaboró la receta en un laboratorio. Y allí tuve la oportunidad de hacer la residencia.

A mí me pareció muy pertinente hablar de la relación entre la porcelana y la cocaína porque aquí en Alemania se dice »oro blanco« a la porcelana y en Colombia se lo dice »oro blanco« a la cocaína: el mismo dicho cuyo significado es en dos países completamente diferente. Pero para mí significa las dos cosas porque estoy y vengo de los dos sitios y la historia de la porcelana en mi familia tiene relación en ese sentido. Entonces, estoy haciendo una obra que tiene referencia con la problemática de la cocaína en Colombia en relación con la historia de la porcelana en mi familia.

La idea era hacer una obra en la residencia y yo he tenido siempre un interés con mi nombre David y con mi identidad y con los diferentes David que han marcado la historia. Por este motivo he hecho David Bowies en porcelana como tazas o Miguel Ángel en tazas y cuando me puse a pensar qué hacer en Meißen dije: de pronto es el momento de hacer un David Torres en porcelana ¿Que puede ser más Kitsch que hacerse a sí mismo en porcelana?. (ríe)

Si ya estamos en un sitio que se representa de alguna manera el Kitsch en Europa, pues entonces esto tiene que ser completamente Kitsch. (ríe)

Entonces voy a poner ciertos detalles que genere un poquito la discusión. Estoy enamorado de la cultura popular, del reggaetón especialmente, su estética y todo lo hace parte de su evolución. Hay mucha gente que ama al reggaetón y hay gente que lo odia, entonces es como estar en un limbo. Entonces si hago a un David reggaetonero es como mostrar un poco la estética exagerada y kitsch que hay en este momento que me interesa.

También tiene que ver mucho con la estética de los narcos. En los videos del reggaetón uno se ve gente con mucho oro, plata, mostrando su riqueza…

Si es una obra autobiográfica me parece lógico que utilices símbolos que representen a tu biografía, a ti y también a tu cultura colombiana que incluye esta estética.

Si, hace parte de lo que me hace latino. El reggaetón es latino. Además, la estética de los reggaetoneros famosos es mostrar lo que tienen y eso era lo que los primeros narcotraficantes también querían. La exageración es lo que me importa.

Además, es un poco alegoría a cómo nos ven en el extranjero. Porque a veces piensan que todos estos gustos son míos, pero no soy así. Tampoco soy una persona que consume cocaína. Pero en varias oportunidades cuando me han preguntado de dónde vengo y dijo que soy un colombiano, lo primero que hacen es relacionarme con estos temas de narcotráfico, con Pablo Escobar. Todo esto son productos que salen de temas cinematográficos y de series que tienen que ver con la narcocultura. Y así es como la gente en el extranjero nos ve.

Pero uno no sabe si está bien identificarse con eso o no, está bien enojarse o no? porque igual el país tiene relación con eso y es algo innegable. Uno no puede tapar el sol con un dedo.

Entonces, la obra es una exageración de mí mismo, pero también una exageración de esta iconografía: los grills, los bling bling gigantes y estas chaquetas llenas de colores y estampados con un montón de símbolos. En los estampados de la Chaqueta de este retrato hay algunos elementos que hacen alusión directa a los eventos o a la estética narco que se desarrolló en los años 90. No me interesan tanto Narcos o la cocaína hoy en día, sino más bien lo que ocurría en la época en la que mi padre trabajaba con la porcelana y cómo se retrataba el fenómeno del narcotraficante en aquella época. Todo el país se vio afectado de alguna manera. Pasaban muchas cosas sangrientas y nadie podía decir nada simplemente por temor. Y uno tenía que dejar andar su vida a pesar de todas estas circunstancias. Entonces la idea es que toda esta iconografía como la chaqueta, hacen parte del imaginario.

Además, estoy jugando con el tema de Marca y mercadeo por esta razón, las espadas cruzadas del logo de Meißen se van a enfrentar con dos pistolas doradas cruzadas que son pura estética narco. También me ha asustado un poco ser tan directo con este mensaje, especialmente porque en Meissen podrían mal interpretarme. Pero ellos entienden de dónde vengo y que específicamente quiero contar. Es una historia que realmente muy pocas personas saben y a mí me parece muy interesante como la estética narco se ha impregnado tanto en las artes plásticas en Colombia.

La pieza se encuentra en proceso y será terminada en los próximos días, en junio o julio 2023 se realizará la exposición con mis colegas donde mostraré el resultado de la residencia. Falta la decoración de la pieza y una última quema en el horno.

Qué crees ¿Cuáles son los desafíos actuales para los artistas cerámicos?

Bueno, uno de los desafíos que uno tiene como artista de la cerámica es no ser encasillado sólo como ceramista. En mis redes digo que soy ceramista, pero no quiero encasillarme como ceramista. El lenguaje de arte tiene que hablar a través de otros materiales y de otras experiencias también. Me parece que lo esencial hoy en día es que el ceramista se relacione con las tecnologías. También es importante saber que nosotros los ceramistas no solamente somos artesanos de poner cosas en una vitrina, sino que nuestras obras son dignas merecedoras de estar en un espacio de exhibición.

Hay otra cosa muy importante sobre todo en Europa que tiene que ver con la materia prima y con los costos energéticos porque todos sabemos que la cerámica se quema en un horno de gas o en un horno eléctrico. Como consecuencia de la guerra entre Rusia y Ucrania, Alemania ha sido afectada directamente en temas energéticos. Los costos de la electricidad o de gas se han duplicado, e incluso triplicado. A mí como artista colombiano que no tiene que ver nada de Ucrania o Rusia he sido directamente afectado, también. Los ceramistas que no son gente con muchos ingresos económicos, incluso empresas más grandes como Meißen o Hedwig Bollhagen, donde trabajo, están muy asustados y están tratando de replantearse muchas cosas porque los costos de funcionamiento de las fábricas se ha incrementado o incluso hasta llegar al punto de no ser suplidos de gas. Entonces la pregunta es: ¿cómo reducir costos y cómo disminuir el consumo de la energía?. Los precios de la materia prima, todos los colores y esmaltes se han incrementado exorbitantemente porque son minerales. Entonces, creo que uno de los desafíos más grandes es como hacer para tener menos impactos con lo que uno consume en el momento de hacer las piezas, como aprovechar los materiales 100 por ciento y usar los hornos de una manera más eficiente, invertir en mejores hornos que consuman menos energía, por ejemplo. Creo que hacer las cosas más sostenibles es un desafío muy grande para un artista que dedica su arte principalmente al mundo de la cerámica.

Otra cosa que me parece muy interesante de este tema es que, como ceramistas, hay que ralentizar los procesos artísticos e incluso nuestros hábitos sobre cómo vemos el arte. Considerando la forma en que interactuamos con las redes sociales hoy en día, creo que este problema es muy relevante.

Si, uno tiene que pensar si vale la pena no solamente con los costos y con el tiempo sino también vale la pena con la idea. Tienes un montón de ideas, pero eres consciente de los costos económicos y energéticos etc.? Cuando cuento mis ideas a las personas hay gente que me dice: »es simplemente hacer, haz las cosas.« Pero no es así, las ideas anotadas en una libreta no son costosas. Pero no es sensato realizar todas las ideas que se me ocurren porque los materiales cerámicos que uso no son del todo baratos. También me doy cuenta de que hay artistas que sacan obras de temáticas de qué está pasando en actualidad en una forma muy rápida. Y si quisiera hacer un trabajo sobre la guerra entre Rusia y Ucrania, por ejemplo, sería posible que la guerra incluso terminara y yo siguiera en pleno proceso de trabajo. Porque los procesos que yo elaboro son realmente de largo aliento. (risas)

David, ¡gracias por la entrevista y estoy esperando ver los resultados de tu trabajo actual!

Dive deeper into the art world

Barbara Evina: »I am just an African woman who happens to make art«

The great cities of the world are shaped by an ever-changing society, and the arts thereby function as a mirror of their changing inhabitants. In this interview series, we let three artists talk whose lives between cultures have brought out exciting artworks.

Golden times: The Fuggers as patrons of the arts

On the 500th anniversary of Jakob Fugger's death on December 30, the Schaezlerpalais is commemorating him as a patron of the arts: the wealthy merchant family commissioned numerous artists of their time. The exhibition Art’s Rich Heritage: Jakob Fugger and his Legacy runs until April 12, 2026, in Augsburg.