- Art.Salon

- Artists

- Albert Gleizes

- Composition rythmique, quatre éléments

Albert Gleizes

Composition rythmique, quatre éléments

Found at

Christies,

Paris

Art Impressionniste & Moderne, Lot 119

10. Apr - 10. Apr 2024

Art Impressionniste & Moderne, Lot 119

10. Apr - 10. Apr 2024

Estimate: XX.XXX

Price realised: XX.XXX

Price realised: XX.XXX

Description

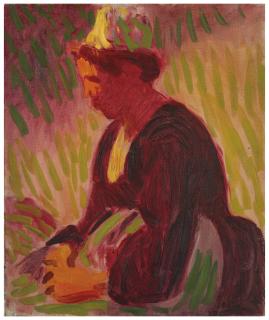

Dans La Peinture et ses lois, Albert Gleizes affirme : «peindre, c’est donner vie à une surface plane ; donner vie à une surface plane c’est transformer son espace en rythme» (La Peinture et ses lois, 1923). Entre 1922 et 1934, les expériences de Gleizes sur la visualisation du rythme expriment l’importance pour lui de l’association de la «translation» et de la «rotation», qui caractérisent bientôt la dimension picturale et l’aspect théorique de son travail. En pratique, cela signifie que si la surface générale est un rectangle, par exemple, la «translation», agréable à l’oeil au repos, est une simple répétition de ces proportions, parallèlement aux bords de la toile, alors que la «rotation» est obtenue en inclinant les plans, vers la droite ou la gauche, de façon à ce que, pour ainsi dire, l’oeil imagine que le plan lui-même tourne et le suive. Cependant, Gleizes rapportera plus tard : «J’ai rapidement compris que je devrais accepter une discipline. J’ai adopté un principe de compartimentation, où les rapports et les proportions s’organisent en harmonie avec le rapport initial de hauteur et de largeur donné par la surface générale à peindre. C’est ainsi que j’ai fait une série de tableaux... que j’ai donc appelés, selon le cas, Tableau avec deux, trois, quatre, sept éléments» (Albert Gleizes, Souvenirs 1934-39). La présente œuvre, qui fait partie d’un certain nombre de variations sur un thème, contient quatre éléments colorés et visuellement divertissants, chacun associant des formes rigides et ondulantes. La « compartimentation » de l’espace par Gleizes, ainsi que l’association entre la juxtaposition de couleurs intenses et de plans mobiles imbriqués qui semblent tourner sur des axes obliques font de Composition rythmique, quatre éléments une oeuvre incroyablement intense du point de vue optique. Composition rythmique, quatre éléments est achevé en 1925, année où le Bauhaus (qui

In La Peinture et ses Lois, 1923, Gleizes asserts that: ‘to paint is to give life to a flat surface; to give life to a flat surface is to turn its space into rhythm’ (Albert Gleizes, La Peinture et ses Lois, 1923). Between 1922 and 1934 Gleizes’ experiments in the visualisation of rhythm were the result of his belief in the importance of the combination of ‘translation’ and ‘rotation’, a belief that would ultimately characterise both the pictorial and the theoretical aspects of the artist’s work. In practice this meant that, assuming the overall surface to be a rectangle, the ‘translation’, appealing to the eye at rest, was a simple repetition of those proportions, parallel to the sides of the canvas, while the ‘rotation’ was evoked by titling the planes, to the right or to the left, in such a way that the eye would, so to speak, imagine that the plane itself was turning, and follow the movement round. And yet, as Gleizes subsequently recounts: ‘I quickly understood that if I was to succeed, I would have to accept a discipline. I adopted a principle of compartmentalisation, with the relations and proportions organised in harmony with the initial ratio of length and breadth given by the overall area to be painted. It was thus that I made a series of paintings…which I called, as appropriate - Painting with two, three, four, seven elements’ (Albert Gleizes, Souvenirs 1934-39). The present work, one of a number of variations on a theme, contains four brightly coloured, visually diverting ‘elements’, each a blend of rigid and undulating forms. Gleizes’ compartmentalisation of space, along with the combination of the juxtaposition of striking colours, and shifting, interlocking planes, which appear to rotate on oblique axes, renders Composition rhythmique incredibly optically galvanising. Composition rhythmique, quatre elements was completed in 1925, the same year in which Gleizes was commissioned by the Bauhaus (where certain ideals an

work of Gleizes and his circle of acquaintance alongside that of Fernand Léger,

Juan Gris, Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso. Like František Kupka, Gleizes too found followers in the early 1920s, namely Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone, former pupils of André Lhote. The dealer-publisher Jacques Povolozky gave Gleizes a platform both for his work and his theoretical writing as did Léonce Rosenberg who included his work in several exhibitions at the Galerie de l’Effort Moderne in Paris as well as publishing the artist’s ntellectual expositions in the Bulletin de l’Effort Moderne. By 1934, feeling that his own work was incomplete and that the methods he had developed, partly through his study of Robert Delaunay’s early experiments in near non-representation (in particular his Formes Circulaires, Disques, Soleils and Lunes of 1913-14), had not succeeded in achieving the desired level of ‘rotation’, Gleizes had taken, as in Composition rhythmique, quatre elements, to adding simple arabesques in grey to previous work, arabesques, ‘which, in a single line, expressed all the comings and goings I had evoked in the painting’ (Albert Gleizes, Souvenirs 1934-39). Realising the rotation he had long sought, Gleizes arabesques unite the composition’s static and mobile elements creating the effect of a thrilling and dynamic whole.

Anne Varichon a confirmé l'authenticité de cette œuvre.

- Paul Rosenberg, Paris. | André Schoeller, Paris. | Marvin Lundy, Philadelphie; vente, Sotheby's, New York, 14 novembre 1985, lot 252. | Acquis au cours de cette vente par le propriétaire actuel.

In La Peinture et ses Lois, 1923, Gleizes asserts that: ‘to paint is to give life to a flat surface; to give life to a flat surface is to turn its space into rhythm’ (Albert Gleizes, La Peinture et ses Lois, 1923). Between 1922 and 1934 Gleizes’ experiments in the visualisation of rhythm were the result of his belief in the importance of the combination of ‘translation’ and ‘rotation’, a belief that would ultimately characterise both the pictorial and the theoretical aspects of the artist’s work. In practice this meant that, assuming the overall surface to be a rectangle, the ‘translation’, appealing to the eye at rest, was a simple repetition of those proportions, parallel to the sides of the canvas, while the ‘rotation’ was evoked by titling the planes, to the right or to the left, in such a way that the eye would, so to speak, imagine that the plane itself was turning, and follow the movement round. And yet, as Gleizes subsequently recounts: ‘I quickly understood that if I was to succeed, I would have to accept a discipline. I adopted a principle of compartmentalisation, with the relations and proportions organised in harmony with the initial ratio of length and breadth given by the overall area to be painted. It was thus that I made a series of paintings…which I called, as appropriate - Painting with two, three, four, seven elements’ (Albert Gleizes, Souvenirs 1934-39). The present work, one of a number of variations on a theme, contains four brightly coloured, visually diverting ‘elements’, each a blend of rigid and undulating forms. Gleizes’ compartmentalisation of space, along with the combination of the juxtaposition of striking colours, and shifting, interlocking planes, which appear to rotate on oblique axes, renders Composition rhythmique incredibly optically galvanising. Composition rhythmique, quatre elements was completed in 1925, the same year in which Gleizes was commissioned by the Bauhaus (where certain ideals an

work of Gleizes and his circle of acquaintance alongside that of Fernand Léger,

Juan Gris, Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso. Like František Kupka, Gleizes too found followers in the early 1920s, namely Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone, former pupils of André Lhote. The dealer-publisher Jacques Povolozky gave Gleizes a platform both for his work and his theoretical writing as did Léonce Rosenberg who included his work in several exhibitions at the Galerie de l’Effort Moderne in Paris as well as publishing the artist’s ntellectual expositions in the Bulletin de l’Effort Moderne. By 1934, feeling that his own work was incomplete and that the methods he had developed, partly through his study of Robert Delaunay’s early experiments in near non-representation (in particular his Formes Circulaires, Disques, Soleils and Lunes of 1913-14), had not succeeded in achieving the desired level of ‘rotation’, Gleizes had taken, as in Composition rhythmique, quatre elements, to adding simple arabesques in grey to previous work, arabesques, ‘which, in a single line, expressed all the comings and goings I had evoked in the painting’ (Albert Gleizes, Souvenirs 1934-39). Realising the rotation he had long sought, Gleizes arabesques unite the composition’s static and mobile elements creating the effect of a thrilling and dynamic whole.

Anne Varichon a confirmé l'authenticité de cette œuvre.

- Paul Rosenberg, Paris. | André Schoeller, Paris. | Marvin Lundy, Philadelphie; vente, Sotheby's, New York, 14 novembre 1985, lot 252. | Acquis au cours de cette vente par le propriétaire actuel.